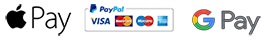

The thing – Albert Monis / Ado Arrietta

17.00€

Albert Monis – Ado Arrietta: The thing

Description

The thing · E. Vila-Matas

Me escribió Albert Monis y me dijo que Arrietta y él se sentirían honrados y contentos y dibujados y fotografiados si escribiera algo al principio de este libro que contenía un universo de imágenes que seguro que estaba en perfecta conexión con mi mundo. Llevaba un documento adjunto con la obra que debía prologar. Y yo pensé: voy a mirar esas imágenes, pero algo que va con Arrietta dentro no es ni necesario que lo vea, seguro que tiene relación con mi propio universo. Aún así, miré lo adjunto; “la cosa”, empecé a llamarlo; poco después, pasó a ser “the thing”.

The thing por aquí y the thing por allá. Me acordaba de “la cosa” cada vez que volvía al ordenador y volvía a entrar en lo adjunto y me veía a mí formando parte de algún modo del libro de Monis y de Arrieta y siendo una cosa más de the thing, aquello que me había llegado adjunto y no sabía de dónde, ni importaba, puesto que el lugar del que viniera no podía cambiar ni un milímetro lo que yo había visto ya y sobre lo que ya había emitido un juicio jubiloso.

Mira —decidí decirle a the thing—, carezco de imagen, tú la tienes y yo no, yo soy sólo pluma y papel, pero lo que escribo refleja el rastro que deja el instante, es dibujo, es fotografía, fue cosa y un día, ahora mismo, será arte.

Dicho esto, me quedé inquieto, reflejando sólo la cara del instante.

Mira —decidí seguir diciéndole a the thing— lo que oyes no está pensado para ser leído, pues, para empezar, quizás no sea exacto decir que está escrito, más bien se ha creado para ser mirado y escuchado, para ser fotografiado y dibujado.

Mira, mírame, fantasma errante en salas de recuerdos, solitario y extraño entre otros extraños, nómada estático en el lugar donde me ves, no puedo asegurar que mis palabras sean arte sobre algo, es decir, arte sobre esto y aquello, arte discursivo, sino el arte en sí, la cosa, the thing, vamos. De eso se trata. Pasa página ya. La puerta que da al mundo está abierta.

Albert Monis emailed me and said that he and Arrietta would be very pleased, honoured, drawn and photographed if I wrote something at the beginning of this book, which contained a world of images perfectly connected with my own. In the letter there was an attachment with the work for which I was to write the prologue. And I thought: I’m going to look at these images, but something that has something of Arrietta’s in it, I don’t even need to see it: it has a relationship with my own universe, that’s for sure. Having said that, I looked at this piece; ‘the thing’, I started to call it; and then some time later, it became ‘the thing’.

The thing over here and the thing over there. I remembered ‘the thing’ every time I went back to the computer, re-entered the file and saw myself as somehow part of Monis and Arrietta’s book; I was one more thing of the thing, of that very thing that had arrived as an attachment from who knew where; what did it matter, anyway, since the place it came from couldn’t change one millimetre of what I’d already seen there and on which I’d already passed a jubilant judgement.

I’m only pen and paper, but what I write reflects the trace left by the moment, it’s a drawing, a photograph, something that was and will one day, at this very moment, be art.

Yet I was worried because this reflection only reflected the face of the moment.

Let’s see”, I decided to continue saying to the thing, “what you’re hearing wasn’t thought up to be read, because to begin with it’s probably not accurate to say that it’s written, but rather that it was created to be looked at and listened to, to be photographed and drawn.

Look, look at me, a ghost wandering the halls of memory, a loner and a stranger among other strangers, a static nomad in the place where you see me, I cannot be sure that my words are art about something, in other words, art about this or that, discursive art or art in itself, the thing, to put it bluntly. That’s what it’s all about. So turn the page. The door to the world is open.

Editor’s note Florent Fajole

Shadow and condensation,

Two authors, Albert Monis and Adolpho Arrietta; but the work is totally one.

The photographs of one and the graphic intervention of the other.

First there are the photographs. Scenes of beaches that Albert Monis then cropped and altered to bring out the few germs he wanted Adolpho Arrietta to take care of.

In the first series, the shadows express something other than the people they project. In this way, they acquire the status of subjects, but they cannot, despite everything, abstract themselves from their causal links. The shadow and the person thus give themselves over to each other, alone or in a group. If the latter reveals itself in its staging, the former can only do so in the form that its silhouette takes. There are no outfits to indicate or facial expressions. The shadow’s form is introspective, yet it manifests an attitude. Who or what is it introspective about? Of itself, perhaps, if we give it enough life, of the person from whom it emanates if we don’t forget that it is precisely a projection of that person. This is the relationship of the double that is so familiar to the human sciences. Who hasn’t felt the dread of seeing their own shadow moving faster or slower than themselves? There’s something dramatic about the simple fact of losing sight of your shadow. Whether it stands back or runs away under the combined effect of the light source and our own movement, we simply feel that a part of ourselves is escaping and that we could lose it forever. What Albert Monis’ images say is precisely that part of our deep interiority that is only expressed when we are on the verge of losing it: the shadow that says something else about us, undoubtedly the most personal.

It is striking to observe the extent to which Adolpho Arrietta has made this relationship his own.

Through the links she establishes in each of the images, she draws dividing lines, associating or distinguishing. She problematises and, in so doing, organises and structures. It’s an editorial act, in the English sense of the word, giving full scope to reading as a critical act and as a device, in the form of series and montage. In other words, it is an act of creation and transformation that questions the very principle of writing through images.

The work underlines the anchoring of the images and explores their possibilities.

The result is a long visual phrase that crystallises from time to time, settling down to slow our gaze and encourage us to pick something up, then leaving again or, conversely, remaining to insist on the base and incise our perception once and for all.

It’s no different in the second series, where this time the figure draws a vertical line as a counterpoint to the horizon line needed to establish a cardinal point of view. The human being thus becomes one of the elements through which we gain access to a spatio-temporal experience. Here again, it is not our straitjacket perspective, as Henri Michaux would say, that distributes the dividing lines; rather, the different inner planes of perception are organised according to the vision of the mind.

But there’s more… In the hypertelic relationships that living beings sometimes have with their environment, and that many writers have explored, there is a supplement that takes the form of a point of condensation through which the individual escapes the inevitability of the divergence of characters.

Signified here by the junction of the cardinal points, at the precise point where the human being enters into excrescence, this solidarity between plane and form unifies the distant and the near, the interior and the exterior. It is comparable to the child’s gaze, which, dense with all that escapes it, temporarily or permanently gives up selling the expanse in order to find its bearings.

Let’s hope that a little play remains for certain privileged people, in the words with which Roger Caillois concluded one of his many texts on mimicry.

Florent Fajole, editor

– Dimensions: Italian style 13 cm (1.5 in) high x 18 cm (7.5 inches) width

– Weight: 180 grammes

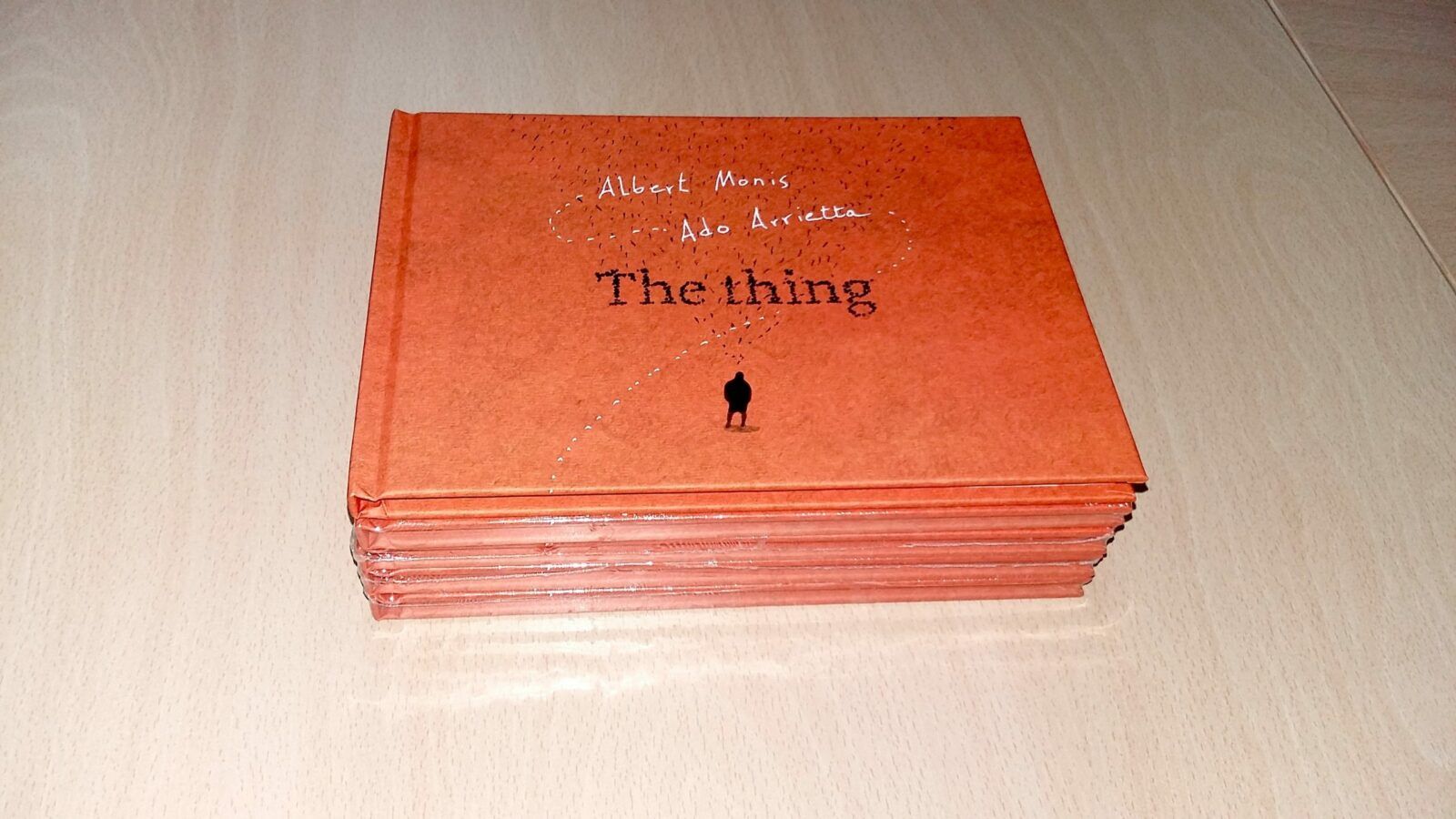

– Number of pages: 40 pages – 4-colour process printed interiors

– Quality: premium paper Gardapat 13 Kiara. Cover with white silkscreen text

Limited edition of 300

Les Editions de la Mangrove, Nîmes et Paris

ISBN 979-10-90202-14-6

With support from the agnès b endowment fund. : www.fondsagnesb.co/2017/01/16/the-thing/

Also distributed by RE:VOIR: re-voir.com/shop/fr/livres/837-the-thing

Additional information

| Weight | 0.18 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 13 × 18 cm |